The combination of climate change and growing demand for fresh water has resulted in an increase in the vulnerability and scarcity of freshwater supplies around the world. The need for fresh water to grow crops and provide for the welfare of the general population, economic growth, and ecosystems is becoming more acute. In the past 50 years, the amount of water withdrawn for human use has tripled (Jordan 2016). Managed aquifer recharge (MAR) is becoming an increasingly important method for improving and supplementing subsurface freshwater storage and ecosystems with an additional benefit of reducing flood risk, managing stormwater, mitigating subsidence, and controlling saltwater intrusion.

This document is intended primarily for state regulators and stakeholders who may not be familiar with the opportunities and challenges associated with MAR. It provides a basic understanding of MAR concepts and example applications. It is important to realize that MAR is an area of active research and expanding practical applications, and that this management process is continuing to evolve with time.

1.1 What Is MAR?

MAR is defined as the purposeful recharge of water to aquifers for subsequent recovery or for environmental benefit (Dillon et. al 2009). Groundwater recharge is a natural phenomenon, and MAR can involve either enhancement or restoration of recharge in areas such as floodplains or introduction of recharge where not naturally present, such as arid environments. Aquifers can provide excellent natural reservoirs for freshwater storage and can be more effective and economical for long-term storage over surface water reservoirs. MAR is a water resources management tool that encompasses a wide variety of water sources, recharge methods, and storage management practices. It has a long history and is likely to see increased use as growing populations create greater demand for water and as a strategy for resilience to adapt to increased vulnerability of water supplies due to climate change (Dillon et al. 2022).

There are many forms of MAR, ranging from infiltration basins and injection wells to managed release from reservoirs coupled with stream channel modification. Each MAR project is designed and implemented based on important location-specific factors, including water rights, regulatory considerations, permitting requirements, source water characteristics, hydrogeologic factors, source water/aquifer interactions, engineering constraints, and economics. Whether a MAR project succeeds or fails is largely dependent on the thorough understanding of project-specific factors. The key elements encapsulating the project factors are intended use, source water, receiving aquifer, and recharge technologies (Figure 1-1. MAR Process Model—Key Elements and MAR Process Model—Recharge Technologies). These are discussed in detail in this document.

Historically, the primary reason to implement MAR has been to increase groundwater storage and alleviate overdraft of groundwater basins. With proper design and successful application, the benefits of MAR can be far-reaching including improving water supply resilience and quality, mitigation of saltwater intrusion, flood control, and freshwater fish habitat improvement (Kirk et al. 2020).

Technical considerations are covered extensively in this document and typically consider a broad range of topics, including permitting, engineering, chemistry, and hydrogeologic factors. Social considerations can range from local acceptance of recharging drinking water aquifers with treated municipal wastewater to flooding idle farm fields with available river flood flows. MAR projects can also have political/regulatory implications; for example, a water replenishment district or stormwater management agency may be required to pay for and maintain MAR projects. Regulatory considerations can range from the right to extract and use stored water to unintended consequences of MAR projects, such as raising the water table under sensitive structures or deep-rooted crops. As will be demonstrated in the case studies in this document, while there are common themes, each MAR application will have a unique set of circumstances that must be identified, understood, evaluated, and planned for.

Figure 1-1. MAR Process Model — Key Elements

Click on the shapes and subject areas in the figure to go to that section of the Guidance

- Confined Aquifer

- Injection well

- Go to Injection well section

- Improving groundwater quality

- Water supply resilience

- Mitigation against saltwater intrusion

- Subsidence reduction

- Unconfined Aquifer

- Infiltration basin

- Go to Infiltration basin section

- Improving groundwater quality

- Water supply resilience

- Mitigation against saltwater intrusion

- Use of storm water

- Use of flood water

- Protection of riparian ecosystems

- Retention structure

- Go to Retention structure section

- Improving groundwater quality

- Water supply resilience

- Mitigation against saltwater intrusion

- Use of storm water

- Use of flood water

- Protection of riparian ecosystems

- Dry well

- Go to Dry well section

- Improving groundwater quality

- Water supply resilience

- Mitigation against saltwater intrusion

- Use of storm water

- Infiltration gallery

- Go to Infiltration gallery section

- Improving groundwater quality

- Water supply resilience

- Mitigation against saltwater intrusion

- Use of storm water

1.2 Purpose/Scope of MAR Guidance

This document synthesizes the current knowledge of MAR, including intended uses, recharge technologies, and technical background, and provides guidance and a framework for considering key elements, such as intended use, source water, effects on the receiving aquifer, and recharge technologies when implementing a MAR project. This guidance document generally follows the flow of typical MAR projects as depicted in the MAR Process Model (Figure 1-1). This process typically starts with identifying the objectives of the MAR project, followed by identifying a source of water and developing an understanding of the subsurface conditions and whether MAR is feasible to implement. Provided MAR is hydrogeologically feasible, the project then addresses site characteristics followed by selection of the appropriate MAR technology. Water rights law and other considerations are beyond the scope of this document but must be considered in any MAR project.

1.2.1 Audience

This document is designed to assist regulators, both state and federal, as well as environmental consultants, local government officials, and other stakeholders to understand the basic principles of MAR projects and highlight key issues and challenges in undertaking and operating MAR projects. This document depicts MAR project considerations through an overview, fact sheets, and several case studies that inform about challenges often encountered when implementing MAR projects and provides the reader with lessons learned.

1.2.2 What the Document Is and Is Not Intended to Cover

MAR is the purposeful recharge of aquifers to increase water supplies for subsequent recovery or environmental benefit. This document provides discussion of the major elements of a MAR project focusing on the intended use of the project, issues related to source water, the receiving aquifer, and recharge technologies used in a MAR project. Case studies are provided to help address lessons learned from ongoing MAR projects.

As stated before, water rights will not be discussed in detail, but are an integral part of any MAR project. Similar to water rights, civil and mechanical engineering and alternative analysis is only briefly discussed in this document. The process and effort required to complete an engineering feasibility study, alternatives analysis, preliminary engineering report, and engineering design with plans and specifications are beyond the scope of this effort. For the purposes of this document, the following engineered infiltration or injection systems are not typically implemented to purposely recharge an aquifer and are therefore not considered to be MAR applications:

- disposal injection wells (for example, underground injection control (UIC) Class I and Class II wells)

- open-loop geothermal systems

- solution mining (UIC Class III wells)

- septic system infiltration drainfields

- CO2 sequestration (UIC Class VI wells)

1.3 Key Terms and Definitions

There are several key terms that are used routinely in discussing MAR applications. Key words and phrases are presented here and supplemented with the glossary near the end of this document.

Advanced treated water (ATW)—Wastewater that has been thoroughly treated by advanced treatment processes to reduce contaminant concentrations (including virus and pathogen reduction) to meet regulatory limits. This water often contains such low levels of impurities (for example, total dissolved solids (TDS)) that it requires conditioning before it can be recharged, as is the case in the use of reverse osmosis.

Aquifer storage and recovery (ASR)—A water resources management technique for storing water underground during periods when there is excess water and recovering that water later, typically facilitated by ASR-specific wells. ASR wells can be used for both the injection of source water and recovery of groundwater.

Aquifer storage transfer and recovery (ASTR)—An ASTR system uses separate injection wells and extraction wells, allowing the injected water to migrate or transfer from the injection area prior to extraction.

Environmental justice — The fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies (USEPA 2023c).

Geochemical compatibility—A measure of the degree to which the source water, aquifer matrix, and native groundwater chemical characteristics will minimize adverse chemical reactions from occurring that could degrade water quality or reduce the recovery of stored groundwater.

Groundwater storage—Water that is stored in an aquifer, whether it is available for extraction or not.

Hydrogeologic conceptual model—Hydrogeologic framework that forms one of the foundational pillars in planning and designing the MAR project. The hydrogeologic conceptual model typically consists of a report that provides the hydrogeologic setting (hydrostratigraphy), receiving aquifer physical characteristics (for example, depth to water, permeability, storage coefficient, degree of confinement), receiving groundwater quality, groundwater flow characteristics (directions, rates, volumes, variability), nearby public and private groundwater users, and groundwater/surface water connections.

Injection wells—As used in this document, an injection well, also referred to as a recharge well, is a bored, drilled, or driven shaft or a dug hole where the depth is greater than the largest surface dimension used to directly supply water into the saturated zone or aquifer(s) for the purpose of recharge or replenishment.

MCL—Maximum Contaminant Levels are standards set by USEPA for drinking water quality. An MCL is the legal threshold limit on the amount of a substance that is allowed in public water systems under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Monitoring—Monitoring is required for MAR projects and often includes routine testing of source water quality and flow rates and performance monitoring of the MAR system, including groundwater quality and groundwater elevations. Baseline groundwater monitoring is also commonly required to establish preproject surface and/or groundwater conditions.

Recharge technology—Any method used to introduce source waters into an aquifer. Technology can range from relatively passive methods, such as farm-flood infiltration, to more intensive methods, such as injection wells.

Recycled water—Treated wastewater that is reused for a new purpose, such as irrigation, potable water supply, or groundwater supply, among others. Sources of wastewater include but are not limited to municipal, industrial, and agricultural wastewater. As used in this document, the term “reclaimed water” has the same meaning as “recycled water.”

Residence time—Length of time recharge water resides in an aquifer before it is extracted. Residence times can be mandated by regulatory agencies to ensure pathogens and other contaminants are filtered from the recharged source water prior to being removed from the subsurface and served as drinking water.

Source water—Source water intended for use as recharge. This can range from transient sources, such as captured available flood flows, to more consistent sources, such as treated water originating from a wastewater treatment plant. Source water availability and quality are key components in the design and implementation of MAR projects. Source water quality can be highly variable and may require treatment or design constraints to improve water quality prior to use in recharge.

UIC—Underground injection control.

Vadose zone—The unsaturated to intermittently saturated zone between the ground surface and the water table.

1.4 State Survey Results

ITRC prepared a MAR survey and distributed the survey to points of contact in each state (see Appendix A. for MAR survey questionnaire). A total of 26 out of 50 states responded to the survey (Figure 1-2). ITRC gathered information on the 24 states that did not respond and supplemented the original database for those states that did respond.

Figure 1-2. State Survey Respondents.

A discussion of the compiled information contained in the database is provided below.

1.4.1 MAR Is Widely Applied within the US

Based on the survey responses and our research, MAR projects were identified in all but 14 states. Figure 1-3 depicts the distribution of states with MAR projects versus states with no MAR projects or where MAR projects have not been confirmed.

Figure 1-3. States with MAR experience.

The most common way to address fluctuating water demand is by implementation of MAR projects (50% of the respondents). This was followed by construction of surface water reservoirs and limited or restricted water use (38%), utilization of recycled water (36%), and utilization of alternative water sources (for example, desalinated inland- or seawater) (32%).

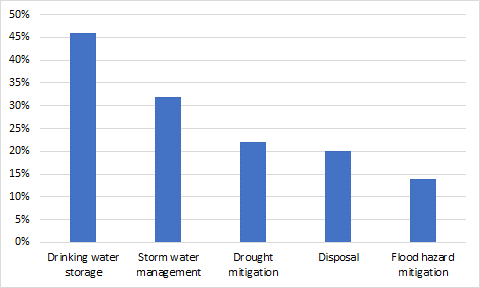

The most common reason that MAR is implemented is for drinking water storage (46%), followed by stormwater management (32%), and drought mitigation (22%). Approximately 20% of the states used MAR for disposal and 14% for flood hazard mitigation (Figure 1-4). Eight coastal states responded that MAR is used to control saltwater intrusion, typically through arrays of injection wells placed along the coastline.

Figure 1-4. Reasons for MAR implementation.

1.4.2 Technical and Regulatory Barriers to Implementing MAR Are Wide-Ranging

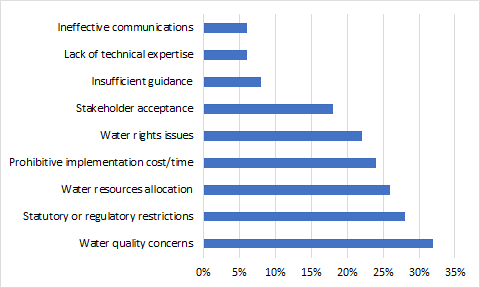

The potential barriers to implementing MAR projects are wide-ranging and should be identified and accounted for early in the project planning and feasibility analysis. While there are common issues on all MAR projects, each usually has site-specific barriers that are often unique to that application. The most common barriers identified in the survey include water quality concerns (32%), statutory or regulatory restrictions (28%), water resources allocation (26%), prohibitive costs or lengthy time to implement (24%), water rights issues (22%), and stakeholder acceptance (18%). Less frequently cited barriers to MAR implementation include a lack of guidance (8%), lack of technical expertise (6%), and ineffective communications (6%) (Figure 1-5). Some states offer grants and other financial incentives to overcome economic impediments such as capital costs to build MAR infrastructure (property acquisition, pipelines, treatment facilities, and wells or basins).

Figure 1-5. Technical and regulatory barriers to MAR implementation.

Contaminants of emerging concern (CEC), such as perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), have had a significant impact on source water quality considerations and potential costs to treat source water prior to recharge, particularly in urban settings (Page et al. 2019; Cáñez et al. 2021). Similarly, ATW, due to its high purity, may require chemical adjustment or conditioning prior to application to avoid potential leaching of trace metals such as arsenic or other contaminants from sediments (Fakhreddine et al. 2015). Each MAR project will likely have site-specific water quality issues that will need to be considered early in the planning process, including the construction of expensive treatment plants. Thorough characterization of source water and receiving water chemistry and receiving aquifer matrix cannot be overemphasized. This is further addressed in Section 3.5.

Water rights are broadly defined as the right to use water from a stream, lake, irrigation canal, or aquifer. While water rights issues associated with MAR projects are specifically not addressed in this document, they can present a significant barrier to MAR implementation, particularly in groundwater basins where the water rights have not been determined or defined. For example, if a stakeholder group or utility desires to pay for and operate a MAR project where they have exclusive use of that additional groundwater, such a requirement could not be guaranteed in areas with unregulated withdrawals. It should be noted that water rights vary from state to state, complicating comparison of individual projects.

1.4.3 Water Chemistry Is a Major Concern

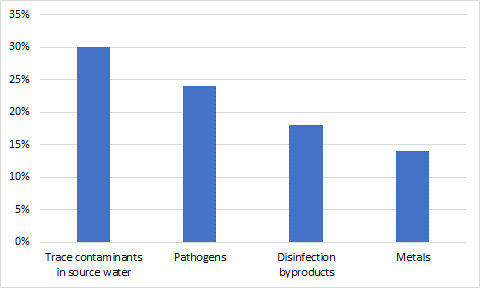

As anticipated, water chemistry is a concern among 34% of the states responding to the ITRC survey. These concerns were focused on source water that contains trace contaminants (30%), pathogens (24%), disinfection by-products (18%), and metals (14%) (Figure 1-6). Many states (30%) responded that they were also concerned with mobilizing aquifer matrix materials such as arsenic.

Figure 1-6. Water chemistry concerns.

1.4.4 Modeling Is an Important MAR Design Tool and Is Used by Most States

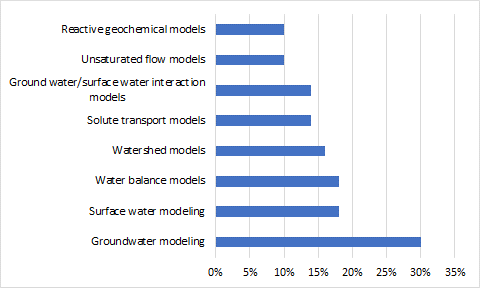

Groundwater and surface water modeling was identified as an important tool in the design, implementation, and permitting of MAR projects. Groundwater and/or surface water modeling is employed by 30% and 16% of the responding states, respectively. Only 10% of the states responded that models are not used on their MAR projects. Depending on the project characteristics and MAR project objectives, other types of modeling employed by states include water balance models (18%), watershed models (16%), surface water/groundwater interaction models (14%), solute transport models (14%), unsaturated flow models (10%), and reactive transport models (10%) (Figure 1-7). A total of 13 states responded that they run models in-house, while 16 may use outside contractors.

Figure 1-7. Modeling.

1.4.5 Many States Provide MAR Guidance Documents

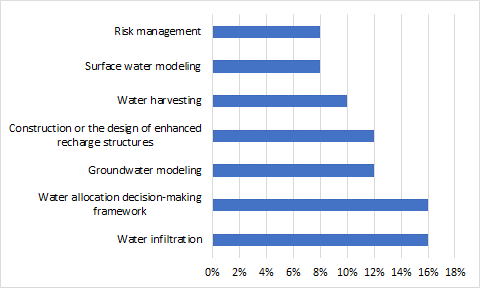

Many of the responding states (92%) have existing guidance documents applicable to MAR projects, with the most common guidance documents regarding water infiltration technologies (16%), water allocation decision-making framework (16%), construction or design of recharge facilities (other than wells) (12%), and groundwater modeling (12%). Other types of guidance documents include water harvesting (10%), surface water modeling (8%), and risk management (8%) (Figure 1-8). Approximately 8% of the states indicated that they have no guidance documents for MAR-related projects.

Figure 1-8. Guidance documents.

1.5 Document Organization

This document is organized as follows:

Section 1: Introduction — Introduces MAR, provides key definitions, discusses current approaches and stakeholders, document organization, and the MAR Process Model.

Section 2: Project Planning — Provides brief description of important aspects of planning a successful MAR project from a project management perspective.

Section 3: MAR Overview — Provides an overview of MAR and multiple forms of MAR, each requiring an understanding of the intended use, source water, receiving aquifer, and recharge mechanism.

Section 4: Recharge Technologies — Provides a series of fact sheets discussing recharge technologies applicable to MAR projects.

Section 5: Case Studies — Provides case study examples of MAR projects and a series of fact sheets regarding each case study.

Appendix A.: Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) State Survey

Appendix B.: Water Quality Parameters

Appendix C.: State, Territory, and Tribe Contacts for Managed Aquifer Recharge